Renewable Energy Production in the West

The deserts of the Southwest are on the threshold of becoming the epicenter for renewable electrical generation in the U.S.

LeRoy W. Hooton, Jr.

May 3, 2010

Water and energy are among one of the most pressing issues facing the U.S. Both are critical to the nation's future – water is essential to life and energy fuels the nation's economy and quality of life. Both resources are of special concern in the semi-arid West (Utah, Nevada, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona and California). All of these states are considered part of the nation's Southwest

|

Concern over water and energy in the West is emerging, in part, because of climate change and the need to replace traditional fossil fuels with clean renewable energy sources. The West is rapidly becoming the mecca for new renewable energy development, particularly solar in the sun-rich and water-scarce deserts.

David Boello, Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, writes in the Yale Environmental 360, “We're not going to solve the [energy] problem without putting large-scale, concentrated solar facilities in the American Southwest.” This may help with the development of renewable energy on the one hand, but on the other hand, it exacerbates the water resource problem in the West. Making a statement of the obvious – there isn't much water in the deserts!

According to the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) National Renewable Energy Laboratory, “... the link between clean, affordable energy and clean, affordable water is crystal clear. There cannot be one without the other.” This fact is reinforced by New York Times reporter Todd Woody, “Here is an inconvenient truth about renewable energy: It can sometimes demand huge amounts of water, [which] ... many of the proposed solutions to the nation's energy problems, from certain types of solar farms to biofuel refineries to cleaner coal plants, could consume billions of gallons of water every year.”

This creates a conundrum: Renewable energy will help provide clean electricity, but it will also aggravate already scarce water resources in the West. Under this scenario, competition for water will be even greater on the Colorado River, which is already over-appropriated and historically a source of contention between the river's various interests. Beginning with the West's mountain watershed states in the north to the desert states in the south, the Colorado Basin is the fastest growing region of the U.S. Adding to the dilemma is the effects of climate change, which is changing the hydrology of the region. All three – energy production, population growth and the effects of climate change are now converging onto the West's desert landscape. The question regarding this conundrum is what does this do to the West's water, land and environment.

An example of the water-energy conflict occurred this past year, when the German firm, Solar Millennium proposed to construct a 268 megawatt solar thermoelectric plant in the Amargosa Valley. Located about 80 miles northwest of Las Vegas, the $3 billion project would consume 1.3 billion gallons of water to cool the solar thermoelectric power generating process. This water demand amounted to about 20 percent of the area's water resources and became the main stumbling block towards Solar Millennium gaining the necessary approvals for the project. The water issue divided the residents; some feared that their aquifer would be depleted and others were concerned about the impact on the endangered pupfish. Those who supported the project did so because of new job creation or the opportunity to cash-in on their irrigation water rights. In this case, the concern over the depletion of the community's water prevailed,

|

Not only are there water concerns, there are environmental one's as well. Advocates of the National Park system have expressed their concern over solar power facilities located in the Mojave Desert. In an article written by Amy Leinbach Marquis appearing in the Winter 2009 National Parks Conservation Association's (NPCA) publication, she raises the question of renewable energy. “California's solar boom threatens the very place it's meant to protect,” she wrote. Marquis further questioned where all the water would come from to cool the number of growing solar thermoelectric facilities. “Where will [the] water come from?... Not enough people are asking these questions,” she quotes Michael Cipra, NPCA's California Desert program manager.

The U.S. is on the cusp of tapping huge amounts of desert sun energy. California's 2003 law requiring utilities to switch 20 percent of their energy to renewables by 2010 (33 percent by 2020) facilitated the current boom in solar activity in the West. Another much larger boom is expected as a result of President Obama's $80 billion for clean energy contained in the stimulus package and his goal to double the nation's renewable energy during the next 3 years. Interior Secretary Salazar has said he supports the construction of new transmission lines to convey this new solar energy from the deserts to major western cities such as Phoenix, Los Angeles and Albuquerque. Like the industrial revolution over a century ago, which transformed the East and mid-West with factories and industries, the West's deserts may well be on the verge of such a revolution, but with large renewable energy farms.

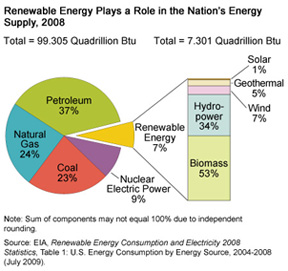

Today, renewable energy is only a small percent of the nation's overall energy production. According to the DOE's U.S. Energy Information Administration, all sources of renewable energy amount to only 7 percent of the nation's total production. Hydropower and biomass contributes 87 percent with solar 1 percent, geothermal 5 percent and wind 7 percent of the total renewable energy. However, the generation of renewable energy is increasing; excluding hydroelectric generation, solar and wind generation increased by 29 percent over the past two years. This growth is expected to increase. According to a citizen advocate group, “Basin and Range Watch,” the Bureau of Land Management has received 130 applications for large-scale photovoltaic and concentrated-solar projects on one-million acres of land in the Southwest.

Two recent renewable energy projects are a solar project in Nevada and a wind project in Utah.

Solar Power Facility in Boulder, Nevada

|

In 2007, Acciona Solar Power, a partially owned subsidiary of Spanish conglomerate Acciona Energy, constructed the 64 megawatt Nevada Solar One project. The $266 million solar thermoelectric project was designed to produce enough solar energy to supply electricity to 15,000 homes in the Las Vegas area.

This solar thermoelectric process is accomplished by reflecting the sun's rays with 184,000 movable mirrors located in parabolic troughs, to thermo tubes that heat an oil medium to 750 degrees Fahrenheit. Then, via a heat exchanger, the heat is converted to pressurized steam, which drives a turbine to generate the electricity. The steam is condensed and cooled and recirculated with make-up water added to the cooling system. Annually, the process consumes 1.4 billion gallons of water supplied from Boulder City's Lake Mead supply.

A major advantage of the solar facility is that it leaves no carbon footprint – the disadvantage for now is the cost of the solar-generated electricity is greater than the current market and must be subsidized. It is believed that in the long-run solar power will cost less than coal-fired electricity.

Earlier this year, Acciona Solar Power received a $2.9 million federal grant to cover 30 percent of the cost of adding 40 new solar troughs.

The Milford Wind Corridor Project in Utah

|

In 2006, the Beaver County Commission issued a Conditional Use Permit to First Wind, an independent North American wind power company based in Boston.

In 2009, the first phase of the project, costing over $400 million, became operational. The facility consisting of 97 turbines, standing on towers 262 feet high, generates 203.5 megawatts of electricity, enough to power 44,000 homes in California.

The electricity is conveyed through a new 88 mile transmission line to the Intermountain Power Project (IPP) located in Delta, Utah; from there the electricity is transported to 44,000 homes in southern California and the cities of Pasadena and Burbank through IPP facilities. This electricity is counted towards the requirement of a California law that requires utilities to switch 20 percent of their electricity supply to renewable energy by 2010.

The Deseret News reported that both the State of Utah and federal government provided tax incentives amounting to about $4.3 million. The incentive offers commercial producers a credit of 0.35 cents per kilowatt hour produced over the first four years of a project's life, in addition to a federal tax credit of 1.9 cents per kilowatt hour.

The project could eventually be built-out with five or six more phases.

A First Wind official touted that an equivalent energy production from fossil fuels would have produced 210 tons of carbon dioxide annually, about as much as the CO2 emitted by 37,000 automobiles.

The use of wind power required no water to generate the electricity.

Conclusion

The West is an ideal location for renewable energy development. At the extreme, some believe that it has the potential to generate enough renewable energy to meet the nation's entire electrical generation capacity, which in 2007 averaged 474 Gigawatt's (GW). It 's estimated that Nevada alone has the sun and land area for potentially 600 GW. Ironically, Nevada is also the driest state in the nation, followed by Utah.

Growth is already creating stress on the West's water resources. Water problems in the West are well known and they will only increase under the collective stresses of energy policy, population growth and climate change.

The development of renewable energy in the West presents enormous challenges, and none are more challenging than water necessary to produce this energy.

![power_plant_5[1] power_plant_5[1]](../images/power_plant_5_1_.jpg)