Interior Secretary Salazar Speaks on Climate Change

New Interior Secretary Salazar sets the tone for the federal government's plans to cope with the Colorado River, which was described as ground zero for climate change. The river is critical to Utah and the Wasatch Front, which by a transbasin diversion depend on this river to supply the Provo River and Central Utah projects. The U.S. Department of the Interior through the Bureau of Reclamation acts as the watermaster over the river basin system including the 1922 Compact, affecting nearly every Utah resident.

January 28, 2010

Interior Secretary Ken Salazar.

LeRoy W. Hooton, Jr.

(Las Vegas, Nevada) - Attendees of the annual conference of the Colorado River Water Users Association held on December 12-14 at Caesar's Palace, heard from Secretary of Interior Ken Salazar via a seven minute video. He was unable to appear in person because he was attending the Copenhagen Global Climate Conference. His message left no doubt that President Obama’s administration is committed to climate change policies and the reduction of the emission of greenhouse gases.

Secretary Salazar, has been on the job since last January when he was confirmed the 59th Interior Secretary. He seems well suited for the position as he has personal knowledge of the issues relating to the Colorado River with his roots deeply planted in the State of Colorado, where his family has farmed and ranched in the San Luis Valley for five generations. His resume includes being a water attorney and director of the Department of Natural Resources in Colorado. At the time of his appointment he was a U. S. Senator for his home state.

“We all have a stake in what we do over the coming months and years to cut carbon emissions,” he said, noting that climate change is already affecting the Colorado River Basin with temperatures in the Basin increasing more rapidly than other regions of the country – resulting in reduced river flows. Supporting this statement, he said that the snow melt is coming earlier and rain is replacing snow, leading climate-change experts to predict potential permanent reductions of 10 to 20 percent of the average flow in the Colorado River.

The Secretary made a plea to the attendees to help address the consequences of climate change by taking action to reduce carbon emissions and at the national level to pass comprehensive energy legislation.

Salazar told the assembled water users that the Colorado River is in the forefront and center of his agenda as Secretary. He urged them, as stakeholders, to join with other stakeholders, including those across the border in Mexico to work together in solving the complex problems facing the users of the Colorado River.

Following the Secretary, Assistant Secretary of the Interior for Water and Science, Anne Castle raised the specter of harsh government measures if all of the delivery and environmental demands on the river cannot be met because of climate change. “There is only one way to accomplish this goal [to meet all of the demands on the river]: and that is through partnerships that bring multiple interests to the table and force agreements that work,” she said.

|

The Colorado River is critical to the State of Utah. And as one of the stakeholders, it will be affected by any strategy, policy or program implemented to manage the river basin. The Colorado River provides water supply, recreation and economic benefits that touch nearly every Utahn.

_____________________________

Addendum: Colorado River Compact (The Law of the River) Summary

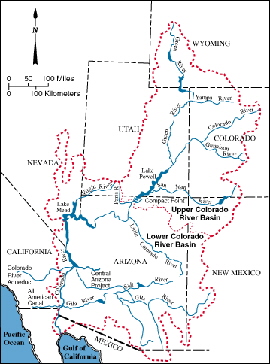

The Colorado River headwaters arise just west of the Continental Divide in Grand County, Colorado, and begin a 1,450-mile journey through seven states to the Republic of Mexico, finding its outlet at the mouth of the Gulf of California and its inlet to the Pacific Ocean.

Water from the Colorado River was first diverted during the late 1800s through a canal constructed through Mexico to California's Imperial Valley. Mexico allowed the canal in exchange for a portion of the water. The Imperial Valley farmers wanted a canal that was within the United States, and in order to accomplish this, enlisted the aid of the federal government. The other six basin states did not want California to build the canal unless their future rights to the Colorado River were protected. This led to the 1922 Colorado River Compact and construction of the "All American Canal" to the Imperial Valley.

Under the 1922 Compact, the waters were divided in perpetuity among the seven states and American Indian tribes. The Colorado River was divided into the Upper Basin (Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming) and Lower Basin (Arizona, California and Nevada). Each basin was allocated 7.5 million acre-feet (MAF) of water annually. Later, under the 1944 treaty, Mexico was guaranteed 1.5 MAF annually, for a total river allocation of 16.5 MAF as measured at Lee's Ferry. The Compact requires the Upper Division to deliver 75 MAF over 10 years, and it's prohibited from withholding the water from the Lower Basin.

The Lower Basin apportionment was determined in the 1928 Boulder Canyon Project Act and confirmed by the Arizona v. California Supreme Court decision: California receives 4.4 MAF and 50 percent of the surplus; Arizona 2.8 MAF and 46 percent of the surplus and Nevada 0.3 MAF and 4 percent of the surplus. As part of Boulder Canyon Project Act, Boulder (Hoover) Dam was constructed in the early 1930s.

|

The Upper Colorado River Compact of 1948 apportions the 1922 Colorado River compact allotment of 7.5 MAF with the first 50,000 acre-feet of water going to Arizona, and the remainder divided with Colorado receiving 51.75 percent, New Mexico 11.25 percent, Wyoming 14.0 percent and Utah 23.0 percent of the river flow. This allocation provides Utah with 1,380,000 acre-feet of water from the Colorado River. Currently the state is using about 950,000 acre-feet of its allotment.

Under the 1956 Colorado River Storage Project Act, Congress authorized the construction of Glen Canyon Dam on the main stem of the Colorado at the Arizona/Utah border and Flaming Gorge Dam on the tributary Green River on the Utah/Wyoming border to capture surplus water during wet winters for use in dry years when supplies are diminished. This provides the means for the Upper Basin states to develop its river apportionment, while fully meeting the allocation obligations of the Lower Basin states.

Since the annual natural flow has only averaged 14 MAF since 1930, and there are additional losses of 2 MAF in evaporation from reservoirs, there is a shortfall in the amount of water available to meet the total demand on the river. This creates an over-appropriated river system that will only be compounded if flows are further reduced by the effects of climate change.