The Owens Valley -- Los Angeles Water Saga

At the turn of the 20th Century Los Angeles began to grow into one of the nation's largest cities, creating the need for additional water supply from the Owens Valley.

LeRoy W. Hooton, Jr.

April 3, 2009

|

Last September, I traveled to Owens Valley to visually observe the effects of one of the most controversial water development projects ever undertaken in the West: the Los Angeles (LA) acquisition of land and water rights in the Owens Valley and the conveyance of this water to LA in the Los Angeles Aqueduct (LAA). The Owens River originates from the eastern slopes of the Sierra Nevada Mountains and flows a distance of about 75 miles to Owens Lake or 225 miles farther south to LA in the LAA to the West's largest megalopolis. This century-old event has become the microcosm for western water wars and the subject of pop art in the making of the movie Chinatown.

Not surprisingly, the acrimonious aftermath of the water grab still lingers today. The clerk at the Best Western Motel in Bishop, laments the loss of the water. She said her elders told her that before the LAA, the valley was green with enormous potential. A car passes by with a “Save Mono Lake” bumper sticker as a reminder of the long battle over LA's driving a tunnel to divert the water from the Mono Lake drainage into the Owens River. LA Department of Water and Power (LADWP) marked vehicles are everywhere in the valley, clearly outnumbering the local authorities in presence. This gives the appearance of a company town.

The Owens Valley is a beautiful area situated between the White Mountains on the east and the Sierra's on the west. Mt. Whitney is the highest peak in the continental U.S. The climate is dry with about 6-inches of annual precipitation. East of the Owens Valley and the White Mountains is Death Valley.

Most of the valley is now owned by LA, or part of the Inyo National Forest. This is apparent as there are few farming operations that can be seen while driving through the valley on US 395. For the most part, the valley is in its natural state and sparsely populated except for three small cities; in the north Bishop, midway is Independence and on the south end Lone Pine. The current population is about 20,000.

Yosemite National Park and Mammoth Lakes are north of the valley and are accessed from the south be traveling through the valley, which has created tourist trade that contributes to the local economy.

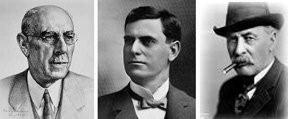

LA’s acquisition of Owens Valley water is usually solely attributed to Chief Engineer William Mulholland. True, he was the head of the LADWP and responsible for the construction of the LLA; but in regards to the acquisition of the Owens Valley water, he was not alone. Three individuals made it possible: J. B. Lippincott, Fred Eaton and William Mulholland.

Both Mulholland and Eaton worked for the privately owned LA Water Company (LAWC) where they developed a professional friendship. Eaton was the superintendent and Mulholland a supervisor. When Eaton left the company in 1886 to serve as LA's City Engineer, he recommended Mulholland as his replacement. Eaton would later be elected Mayor (1898-1900). In 1902, LA purchased the LAWC and hired Mulholland as Chief Engineer and established a governing board to run the new municipally owned waterworks, which in 1904 was renamed the LADWP.

|

Eaton envisioned a joint private-public venture with himself and LA, which Mulholland rejected. Also, he purchased Owens Valley property for himself at his expense. Later, when Eaton offered to sell his valley property to LA, Mulholland refused to pay the asking price. This caused a falling-out between the two colleagues that lasted for the remainder of their lives. Eaton refused to attend the 1913 ceremony of the Owens Valley water arriving at LA through the completed LAA, even though it was his idea and made possible by his efforts. Nevertheless, there was great affection between the two men. “God bless him! I'd like to see a monument a mile high in his honor when the aqueduct is done,”

|

With the passage of the 1902 Reclamation Act, engineer J. B. Lippincott was recruited by the Reclamation Service to head the California program. As a condition for accepting the position, Lippincott was allowed to continue to work for his private engineering firm (Lippincott and Parker Consulting Engineers) on a part time basis. Lippincott considered himself an Angeleno, moving to LA in the early1890s. He knew both Mulholland and Eaton, as they traveled in the same business and social circles. Also, he was well aware of the water problems facing LA. Subsequently, Lippincott found himself working for two masters – LA and the federal government, resulting in a conflict of interest that would influence the outcome of the Owens Valley water.

In 1903 the Reclamation Service began a preliminary reconnaissance study of the Owens River Valley for the purpose of determining a possible local irrigation project. Lippincott selected Jacob C. Clausen to conduct the study.

When the Owens Valley reconnaissance study (Clausen Report) was completed in 1905, the findings were favorable for a reclamation irrigation project, consisting of a 260,000 acre-foot reservoir and a network of canals to irrigate thousands of acres of land. The Report was not yet published, but the Reclamation Service made it available to LA to the detriment of the Owens Valleyite’s best interests. The irony of the report is that it was intended to help the valley’s residents with a federal irrigation project, but contrarily, the engineering data convinced LA officials to move forward with acquisition of the valley’s land and water rights. Adding to the controversy, Lippincott's engineering firm was hired by LA to conduct a study of the LAA and paid $2,500.

Lippincott's action set off a fire storm. Viewed as a hero in LA, he received condemnation from both Owens Valleyites and the Reclamation Service. The Inyo Register gave him the nickname “Judas B. Lippincott.” In an internal Reclamation Service memorandum, it was recommended that for Lippincott's duplicity he should be separated from the Service. Continuing, “Mr. Lippincott has allowed the U. S. Geological Survey and U. S. Reclamation Service to be made use of for the private purposes of the City of Los Angeles.”

As the controversy brewed, LA moved steadily forward with its goal of acquiring water from the Owens Valley and conveying it to LA. In September 1905, a $1.5 million bond election passed for the purpose of acquiring lands, water rights, rights-of-ways and other property, and constructing ditches, canals, tunnels, and other water works to provide water to LA from the Owens Valley. With the bond proceeds, LA executed the Owens Valley water and land options that Eaton had earlier acquired, which at that time gave LA the upper hand. The fait accompli was achieved in 1906, when Congressional legislation granted the necessary rights-of-way over federal lands and then in the following year when the LA voters approved a $25 million bond to construct the LAA.

|

At the recommendation of Lippincott on July 3, 1907 the Reclamation Service formally abandoned the Owens Valley irrigation project. Thereafter on July 31, Lippincott resigned from the Reclamation Service and was hired as Mulholland's deputy. He was defiant of his critics saying, “I would do everything over again, just exactly as I did.” He remained with the LADWP until the completion of the LAA in 1913, when he returned to private consulting work in LA. Lippincott passed away in 1942 at the age of 78.

Mulholland had a commanding presence, was a tireless worker, strong in will and politically savvy. He was described in a term used today as a man's-man. He enjoyed the support of Angelenos and the 19 different Mayors he worked for in his 40 year career. Mulholland's reputation as a water legend was galvanized with the construction of the 225 mile LAA, which was built on-budget in 6 years, though some of the most difficult terrain in North America passing through several mountain ranges, hills and the Mojave Desert. Notwithstanding Mulholland's supporters, there were his critics who describe him as bullish, heartless and ruthless as the chief strategist of LA's acquisition of Owens Valley's water.

At the end of Mulholland's career, on April 28, 1928 the Saint Francis dam he built failed killing over 450 people and destroying 1,200 homes. Mulholland was devastated over the disaster – it was said aging his face 20 years. This once powerful and adulated man became morose as he slipped into old age and eternity. Mulholland said that he had a dream that he and Eaton were walking together – young and virile as both had once been – but he recognized in the dream that they were both dead.” Fred Eaton died in 1934 at the age of 79, and according to his obituary, “...bankrupt and ... [his] finances... having been reduced by ill fortune to approximately nothing” Mulholland died a year after Eaton at the age of 80. He had said, “I want it written on my monument that I helped to build the Aqueduct.”

Mulholland is an LA icon, known as the father of the city's water system that today serves a population of 4 million people and the builder of the LAA, which in its time was compared in magnitude to the construction of the Panama Canal. A street, school and Memorial Fountain park are named after him. In the Owens Valley, there are no monuments erected by its residents paying tribute to Mulholland; however, the LAA is a constant reminder to them of Mulholland and the sordid history of their water.

I was taking photos of the Owens River near Bishop, when a cyclist passed me and then circled around to strike up a conversation. He broke the ice by asking what kind of camera I was using. I told him and then said that I was visiting the area to see for myself the valley and the effects of the LAA. During the conversation, I noted that after visiting the valley I believed that in some respects the residents of Owens Valley, notwithstanding the history of its land and water, may have gotten the better of the deal. The valley is the antithesis of LA, which is crowded, plagued with traffic, pollution and all of the ills of modern urban life. The cyclist didn't disagree.

Select References: Vision or Villainy – Origins of the Owens Valley-Los Angeles Water Controversy, by Abraham Hoffman; William Mulhlolland – And the Rise of Los Angeles, by Catherine Mulholland; and Cadillac Desert by Marc Reisner.