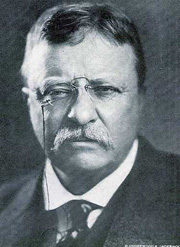

President Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt, America’s Conservationist

A century ago, President Teddy Roosevelt (1858-1919) left office bequeathing a legacy changing America and benefitting Utah and other western states.

LeRoy W. Hooton, Jr.

January 26, 2009

Roosevelt’s likeness is chiseled into stone at Mt. Rushmore and Teddy Bears are named after him. Known for his bravery in the charge on San Juan Hill, he was the 26th President of the United States and one of the nation’s first and most effective conservationist. His legacy can be seen every day by the water we use, the food we eat and the forest lands we enjoy.

|

At the turn of the 20th century, there was a sharp turn in public policy regarding the nation’s resources when President William McKinley was assassinated and Roosevelt ascended to the presidency.

In his first speech to the Congress on December 3, 1901, Roosevelt proclaimed a policy that reversed the historic notion that the nation’s resources should be exploited in the name of progress and nation building. “We are prone to speak of the resources of this county as inexhaustible; this is not so,” he said later in his presidency.

Roosevelt’s speech to Congress outlined a conservation agenda that became the foundation for wiser management of the nation’s resources, with the federal government taking an active role in accomplishing this new policy. He proclaimed that the nation’s resources should be protected for future generations. Later in his life he said, "The nation behaves well if it treats the natural resources as assets which it must turn over to the next generation increased, and not impaired in value.” The values of protecting and passing on the nation’s land, forests and water to future generations were underlying principles that guided his life and presidency. As President, Roosevelt viewed himself as the chief steward of the nation’s resources and used the bully pulpit to shape public opinion and effect change.

Known for his conservation ethic, Roosevelt sought balance between using resources and protecting them; particularly, in the West, where he understood both the beauty and harshness of the region west of the 100th Meridian. He supported the Reclamation Act and forcefully encouraged its passage. “The reclamation and settlement of the arid lands will enrich every portion of our county,” he said.

Perhaps his endearment to the West came from numerous visits to this region of the nation and several years of ranching in the Dakotas, where he grew to understand the limitations arid conditions imposed on farming and wildlife. The reclamation bill provided revenue from the sale of public lands in non-arid states to be used for dams and reclamation projects in sixteen western states. The projects consisted of dams to capture stream flows for farming and power generation. There was opposition by eastern legislators, led by speaker of the House Joe Cannon, but Roosevelt convinced opponents to support the bill, and it was passed. We will never know if the Reclamation Act would have passed if McKinley was president. There are indications that he showed little interest it; therefore one wonders if he would have vigorously urged Congress for passage of the bill. Notwithstanding, it was passed through Roosevelt's efforts.

The Reclamation Act has left a lasting legacy: a water supply for 31 million people, irrigation of 9.2 million acres of farmland and the generation of electrical power for 6 million homes. Utah reclamation projects provide 240,000 acre-feet of municipal water supply for a million people and 430,000 acre-feet of irrigation water reclaiming 330,000 acres of land in the state.

Salt Lake City directly benefits from the Reclamation Act. The Metropolitan Water District of Salt Lake & Sandy delivers water to the City from the Provo River Project and the Central Utah Project, both built by the Bureau of Reclamation.

Besides Roosevelt’s efforts to reclaim the West, he is best known for his policies regarding the nation’s forests, in which he took special interest. In his 1901 speech to Congress, he noted a changing America in respect to the national forest. “Public opinion throughout the United States has moved steadily towards a just appreciation of the value of forest,” he said. He believed that forests are natural reservoirs that conserve water.

Roosevelt reorganized the federal bureaucracy to give the Bureau of Forestry more authority to manage the forest reserves in a scientific manner (Later the Bureau of Forestry would be changed to the United States Forest Service). He selected the forest expert Gifford Pinchot to run the Bureau. Roosevelt gave his full support and confidence to Pinchot as the protector of the nation’s forests. His said, “Gifford Pinchot is the man to whom the nation owes most for what has been accomplished as regards the preservation of the natural resources of our country … He was the foremost leader in the great struggle to coordinate all our social and governmental forces in the effort to secure the adoption of a rational and far-seeing policy for securing the conservation of all our national resources.”

Roosevelt, further protected more public lands by classifying them as “forest reserves,” under legislation Congress passed in 1891. He used the law to increase the reserve by 150 million acres, three times the existing reserve of 50 million acres. In doing so, he angered Congress who passed an Act diminishing the president’s authority to reserve forest lands. Roosevelt set aside another 16 million acres in the forest reserve before signing the new Act.

He also increased the number of national parks, monuments and bird reservations.

In 1906, Salt Lake City and the federal government began a long-standing relationship when Roosevelt, through proclamation, created the “Salt Lake Forest Reserve,” which covered all of the canyons, except Little Cottonwood Canyon. The Forest Service and City cooperated in managing the City’s watersheds to protect the forest and city watersheds, and drinking water supply.

The Salt Lake City – Federal Government partnership was enlarged by an agreement signed on October 7, 1912. The Forest Service agreed to employ three officers for patrol and protective work. Both agreed to protect the land from trespasses and each to prosecute the offenders under applicable state and federal laws. The Forest Service planted trees and the City paid the cost of trees planted on non-federally owned city watershed lands.

The relationship was further strengthened by acts passed in 1914 and 1934 to protect all of Salt Lake City’s canyon watersheds and drinking water supply.

Salt Lake City’s canyon watersheds are now part of the Unita-Wasatch-Cache National Forest.

The legacy of Roosevelt’s resources conservation programs can be seen today in many ways, especially the 150 national forests and 24 reclamation projects he established during his administration His belief that the federal government had a responsibility for conserving and protecting natural resources has made a better and prosperous America. As Roosevelt said, “As a people we have the right and duty… to protect ourselves and our children against the wasteful development of our national resources.”