Colorado River Sustainability Questioned

Will the Colorado River continue to adequately meet the basin’s water needs into the future?

LeRoy W. Hooton, Jr.

March 26, 2008

|

Inasmuch as the Colorado River Basin is tied together physically by the river and legally by compact, what ever happens on the river will affect all of the Colorado River Basin water users.

Background

The Colorado River is the lifeline for the southwestern U.S., providing precious water to this semi-arid region of the nation, which is growing in population faster than the U.S as a whole. With precipitation at only about 4 inches of water annually, the lower basin states depend on the Colorado River for their existence. Approximately 90 percent of the Colorado River flow consists of snowmelt from the upper basin watersheds of Utah, Wyoming and Colorado.

The Colorado River water supply provides drinking water to over twenty-five million people, irrigates 3.5 million acres of farmland and generates 12.2 trillion kilowatts of electrical power from the head of the water held behind Bureau of Reclamation dams.

The waters of the Colorado River are allocated to each of the seven basin states under a 1922 compact. The compact divides the river into the upper and lower basin states. Wyoming, Colorado, Utah and New Mexico are the upper basin states; while Nevada, Arizona and California are the lower basin states. Under the compact 7.5 MAF is allocated to each of the upper and lower basin states and 1.5 MAF to Mexico under an international treaty, for a total allocation of 16.5 MAF. It is recognized that the river is over allocated as the normal flow of the river is closer to 15 MAF, leaving an imbalance between supply and demand even in normal years. This imbalance is exacerbated during drought years.

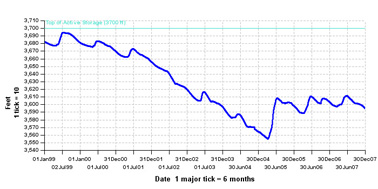

Beginning in 1999, the Colorado River Basin experienced five consecutive years of below-normal precipitation, resulting in plummeting water levels in Lakes Powell and Mead to 38 percent and 54 percent respectively in 2004. During this period the river average flow volumes were about 10 MAF compared to the normal flow of 15 MAF. Moreover, the dryness caused devastating wildfires throughout much of the West. Between 2000-2007 in only 2005 the river flowed above average, at 105 percent. Currently Lake Powell is 45 percent full and Lake Mead 50 percent.

Bureau of Reclamation officials have maintained that the Colorado River system has performed as it was intended during the drought and that the project facilities were able to fulfill all of the compact’s delivery obligations. However, as a result of meeting the delivery obligations, the water storage in Lakes Powell and Mead were greatly reduced. In 2005 Secretary Norton

|

Is Utah's Colorado River Allocation at Risk?

The Colorado River provides water supply to Utah and the Wasatch Front. The Metropolitan Water District of Salt Lake & Sandy (MWDSLS) receives water from both the Provo River Project and Central Utah Project, which are both supplied water from the Utah’s allocation of the Colorado River. MWDSLS delivers water to Salt Lake City and Sandy City and surplus water to others along the front. Clearly Utah and the Wasatch Front have a major stake in the Colorado River.

Utah's view of the situation was discussed by Utah Division of Water Resources director Dennis Strong at the 2008 Utah Water Users Association Workshop held in St. George, Utah. Strong noted that the Colorado River compact is a dynamic document and the recent shortage agreement and interim guidelines demonstrate that the river managers are capable of adapting to changing conditions. The new interim guidelines establish rules for the operations of Lakes Powell and Mead and shortage allocations among the lower basin states. “These guidelines are a significant change consistent with today's needs,” said Strong, adding, “Especially consistent with the Upper Basin's need to protect their allocations into the future, and the Lower Basin's need for developing new water supplies. Lakes Powell and Mead will now be operated by water elevations, rather than by compact allocations.”

In regard to the possibility of developing new water to augment the river, “Who knows what will happen,” said Strong, “...things that sound wild or crazy today may be possible in the future.” His prognostication and the adage that “Necessity is the mother of invention” may both prove true. Just recently it was reported that Orange County, California, opened the world's largest water purification “toilet-to-tap” system in the U.S. The treated water will be injected into the ground water aquifer that provides drinking water to one-half million residents.

In regard to the Scripps’ study, Strong did not discount the enormous challenges facing the river users, but asserted that the basin states are responding to the challenges as demonstrated by the cooperative changes contained in the landmark shortage agreement signed in December. If the reservoirs continue to decline, Strong says action will be taken to prevent draining them. “We recognize that it may be necessary to take shortages – we won't let the reservoirs go dry,” he said.