Thirties Drought Still Utah’s Worst

Drought affected the Great Basin and Southern Great Plains during the mid-thirties.

LeRoy W. Hooton, Jr.

August 14, 2003

Record temperatures and below normal precipitation describe Utah’s weather during the past 5 years. This past July was the warmest ever with an average temperature of 83.4 degrees. The current 5-year drought has emphasized the importance of water conservation and long range planning to accommodate the state's future growth. Even though the 1999-2003 drought has made a strong impression on contemporary Utahns residing along the Wasatch Front, it has nevertheless, not been the most severe drought recorded. During the 1930s, Utah experienced the worst drought on record. Likewise, during this same era drought plagued other regions of the United States.

Water development since the 1930s drought has, through trans-mountain diversions, brought substantial amounts of foreign water into the Wasatch Front. Despite enormous population growth over the past 70 years, these imported water supplies and related storage facilities have greatly mitigated the effects of this and future droughts.

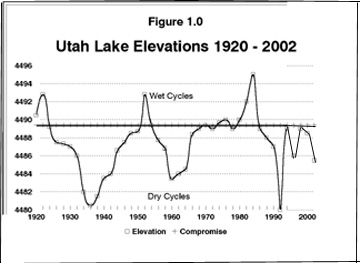

During the 20th century, there have been both wet and dry cycles. The levels of the two main bodies of water, Utah Lake and the Great Salt Lake, record these cycles.

|

The 1930s drought covered large regions of the United States west of the Mississippi River, including the Great Basin, Upper Colorado Basin, Upper Mississippi Basin and Arkansas - White - Red Basins. The drought peaked in 1935-36. According to Palmer Index data from the National Drought Mitigation Center (NDMC), many basins experienced multi-year droughts. For example, the Lower Colorado Basin drought only lasted 3-years, while the Upper Mississippi Basin suffered drought conditions for a decade. NDMC Palmer Drought Severity Index maps indicate that the drought along the Wasatch Front was more severe from 1928 –1934, and continued to a lesser degree from 1934-1939. The drought that created the “Dust Bowl” in the Great Plains lasted from 1934-1939, with 1936 being the most severe.

The Dust Bowl was memorialized by John Steinbeck's classic The Grapes of Wrath. His 1939 book described the drought's impact on farmers in Oklahoma and the Joad family's odyssey to California to find a better life. Drought, farming and cultivating practices created the Dust Bowl within the southern region of the Great Plains. Soil erosion coupled with winds created great dust storms; one storm in 1934 carried topsoil 1,500 miles away to the Atlantic coast states. Described as "Black Sunday," on April 14, 1935, day turned to night as dust clouds plunged Boise City (located in the panhandle of Oklahoma) into total darkness. It is estimated that 80 percent of the land covering 90 million acres was affected by soil erosion. Steinbeck spoke to the social issues related to the drought and depression years. The plight of the thousands of farmers located in the Dust Bowl and their subsequent survival was seen through the eyes of the characters in his book. Steinbeck’s characters remain in print; however the conditions, other than drought, that contributed to the Dust Bowl have been corrected by new farming methods and soil conservation measures.

Along the Wasatch Front, the effects of the drought were severe. Utah Lake, the source of irrigation water for farmlands in Salt Lake County, was too low to be pumped into the Jordan River for diversion to various mutual irrigation companies. A drought relief project was built on the west side of the lake where there was an isolated pool of water deep enough to tap. The Pelican Point Pump Plant and 12,000 foot conveyance channel were constructed at a cost of $183,000 under a state drought relief program. In 1934, Governor Blood and his entourage inspected the project by driving over the dry bed of Utah Lake (See picture). Salt Lake City drilled deep wells and purchased the artesian basin south of the city to bolster municipal drinking water supplies. In 1928, the City had conducted a master plan to development enough water to support a population of 400,000 people. The drought provided the impetus to take action on the plan.

In 1935, the drought sparked public support for the Provo River Project. The Project developed a new water supply by importing water from the Weber and Duchesne Rivers through trans-basin diversions and diverting surplus water from the Provo River. Pushed by Salt Lake City, the Provo River Water Users Association sponsored the Bureau of Reclamation Project, which included the construction of Deer Creek Reservoir on the Provo River. The Metropolitan Water District of Salt Lake & Sandy is the largest stockowner with 61.7 percent ownership. On an annually basis, importation of foreign water from the Provo River Project amount upwards to 55,000 acre-feet.

|

Additionally, water from the 1905 Strawberry River Project is imported from the Strawberry Reservoir and tunnel to southern Utah and Juab County water users. Under the water rights of the Strawberry Water Users Association over 60,000 acre-feet of foreign water is imported to the Wasatch Front.

Unquestionably the importation of foreign water to the Wasatch Front has tempered the current drought. Foreign water diversions amount to about 200,000 acre-feet per year. Had the projects that deliver these waters not been built, the Wasatch Front would be experiencing substantially more severe drought consequences. Equally as important, are the storage and conveyance systems associated with these foreign water projects that physically allow large quantities of water to be stored during normal periods and released during water short periods.

Many probably cannot remember the 1930s drought. We tend to think that things are pretty bad in terms of today's drought; however, looking over the longer period of time, we have experienced drier periods. The 1930s drought affected large regions of the nation, reaching far beyond our state’s borders. Vast areas of the West and southern Great Plains suffered through this extensive drought. Populations were displaced, farmlands lost, and some stipulate that the farming disaster of the Dust Bowl helped push the nation further into the “Great Depression.” So in perspective, the current drought both in Utah and nationally doesn't measure up to the drought of the thirties. Nevertheless, as we did in the thirties, we need to act on lessons learned from the current drought. In Utah water conservation and prudent management of our existing resources will prepare us for future growth and in coping with drought cycles.