U.S. News & World Report

May 19, 2003

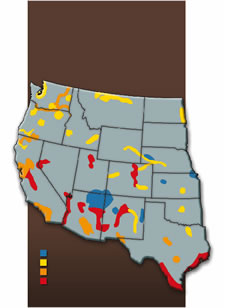

How drought is changing the American West

By Alex Markels

The blizzards that dumped 8-plus feet of snow on Colorado in March and April were too little, too late for Ron Aschermann, a fourth-generation farmer in southeast Colorado's parched Arkansas Valley. After four years of drought, he and scores of other area farmers had already given up on planting this spring. For the moment, he says, "there's water to start a crop." The Rocky Ford Ditch, an irrigation canal in which he shares the water rights with 51 other farmers, is brimming with mountain runoff. Yet Aschermann fears a repeat of last summer, when the ditch ran dry in July and farmers went six weeks without a drop. "The crops just burned up," he says.

So Aschermann and his fellow shareholders in the ditch are packing it in. Rather than endure another year trying to coax onions and alfalfa from the bone-dry earth, they have decided to sell their water rights for $19 million to the thirsty Denver suburb of Aurora. The controversial transfer, now under review by a state district court judge, would reduce the already-beleaguered valley's farm production by about 2,600 acres. Diverted 160 miles north to fast-growing Aurora, the water would be enough to supply about 12,000 households during what could be another scorching summer.

Shriveled. Although spring storms have caused flooding in parts of the Midwest and replenished some eastern reservoirs, much of the West remains gripped by drought. Despite late-season snows, reservoirs in cities like Aurora remain less than one-third full, and even average precipitation won't refill them for three years or more. Unfortunately, National Weather Service forecasters now predict a return to dry weather in much of the region, all but guaranteeing more of the water shortages that have already cost residents from Colorado to California billions of dollars in water bills and shriveled vegetation.

While some climatologists blame global warming for the drought's severity, such episodes are hardly a new phenomenon. Studies of ancient tree rings suggest that dry spells have plagued the West for centuries. A megadrought about 700 years ago may have contributed to the disappearance of the Anasazi Indians, the region's first known human settlers. And three droughts over the past century-including the one in the 1930s that spawned the Dust Bowl-devastated agricultural life across the West, driving out homesteaders and shuttering towns.

|

Until recently, Westerners could avoid this looming problem. Lulled by nearly two decades of above-average precipitation that preceded the current drought, cities like Aurora failed to acquire the water supplies needed to keep pace with their booming populations. Meanwhile, residents-millions of whom migrated from the East in recent decades-have landscaped homes and businesses as if they still lived in wetter climes, carpeting thousands of square miles with bluegrass lawns and other thirsty vegetation.

Even less frugal are many western farmers, whose crops consume about 90 percent of the region's water supply. Blessed by their forefathers with first dibs on cheap water subsidized, in part, by huge federal water projects, most have had little incentive to install water-saving technologies, such as drip irrigation systems. In recent years, total cultivated western acres have actually increased, further squeezing water supplies.

Conservationists, too, are demanding a share of the West's water supply. From New Mexico to Oregon, a slew of enviro-backed lawsuits are forcing farmers and developers to surrender some of the water they've nabbed to the needs of rare fish and other wildlife. The drought has brought all this to a head, touching off the sort of contentious water wars described by Mark Twain more than a century ago. In the West, the author reportedly remarked, "whiskey is for drinking; water is for fighting over."

Rising tensions. In places like Santa Fe, N.M., "water police" now patrol the streets handing out steep fines to scofflaws who violate watering restrictions. A recent 47 percent hike in water rates and the government-mandated retrofitting of 8,000 homes with low-flow toilets have helped reduce per capita water consumption to about 150 gallons a day. But with developers still building to accommodate a countywide population that has grown nearly 75 percent since 1980, tensions are rising. "People are getting sick and tired of bucketing water from their showers just so the developers can build the next big home or subdivision," says Patti Bushee, a Santa Fe city councilor.

In a recent showdown with developers, she and three other city councilors pushed for a new ordinance that would have put a temporary moratorium on construction. Her opponents, who ultimately defeated the measure, flooded the city with building permit applications in case it passed. "So now we have lots more new homes being built," complains Bushee, "but not enough water for the people who already live here."

Aurora resident Ed Wirth sees his lawn and backyard garden threatened this season, while his water bill surges as a result of summertime surcharges of up to 200 percent. "If things are really so bad, then shouldn't we just stop all the new construction, like right now?" Wirth asks.

With Aurora facing another parched summer, the answer might seem an emphatic "yes." Yet city water officials say the problem isn't new houses; it's the greenery surrounding them. According to Peter Binney, Aurora's utilities director, about half the city's water goes to landscape irrigation. "We don't have a water shortage," he says; "we have a water allocation crisis."

Increasingly, experts concur that new strategies for divvying up water are the key to resolving water problems. "The truth is, we've got oodles of water for urban growth," says Charles Howe, a water resources economist at the University of Colorado-Boulder. "Even if you buy just 10 percent of the agricultural water, you've got enough to double the supply for urban and industrial uses." Such transfers can require pipeline extensions and other tweaks to water delivery systems, as well as some swapping between the government agencies and utilities that manage much of the water's flow.

Cheaper, too. Yet they are far less expensive and controversial than the alternative: building big new dams and reservoirs. "The era of big new water projects is over," says Melinda Kassen, a water attorney with the river-protection group Trout Unlimited, which helped defeat Colorado's Two Forks Dam, one of the last big water projects proposed in the West. "It just so happens that it's far cheaper for cities to buy agricultural water."

Ron Aschermann and the other Rocky Ford Ditch shareholders are eager to sell. But some of their neighbors in the Arkansas Valley worry that transferring the water rights to Aurora would devastate the local economy. "Our lifestyle would literally dry up and blow away," says Bob Rawlings, publisher of the local newspaper, the Pueblo Chieftain, who has waged an angry campaign to stop the sale. "When you take water out of the valley, you rob us of our lifeblood. Without water, the farms dry up. Then all the businesses that rely on them go. Then the tax base and the economy go, too."

He points to nearby Crowley County, where farmers sold their water rights to cities 20 years ago. "They turned that beautiful farmland into a desert and the community into a bunch of derelict buildings," says Rawlings. He and other community activists have lobbied for state legislation to block water holders from transferring rights to buyers outside their areas. Others back stiffer laws requiring those transferring water to pay for economic losses to the community.

But such measures undermine farmers' incentive to use supplies more efficiently and hamper an open market for water, say some experts. If farmers can sell their water rights freely, "water will flow to its highest-valued use," says Bennett Raley, the Interior Department's assistant secretary for water and science. The agency's just announced Western Water Initiative promotes a market-based system where farmers can sell water rights (a step that now requires court approval) or temporarily lease them to "water banks," creating spot markets where water can be traded among farms, cities, and environmental interests. "In some years farmers will choose to grow crops," says Raley. "Other years they'll take a check."

That is what Raley envisions for southeastern California's arid Imperial Valley. Its farmers receive about a trillion gallons of water annually from the Colorado River to water alfalfa and other crops. The irrigation project is among the nation's largest and least efficient. Things are about to change, however, because of new federally mandated reductions that require both the valley and neighboring San Diego (which also draws heavily from the river) to decrease their combined consumption by 15 percent.

Urban shift. Ed McGrew, an Imperial Valley farmer, is resigned to giving up some of his water. "Most of us realize it's inevitable that more water is going to be transferred from agriculture to cities," says McGrew, who runs a 1,400-acre farm near Holtville. To save water, he has already invested in a drip watering system for his asparagus field and pump-back systems to recirculate water used to irrigate his alfalfa crop. If San Diegans will pay Imperial Valley farmers to give up part of their allotment, "I'd have no problem taking my share of the money and investing in more conservation," he says.

But some of those who have spent a lifetime working the land are determined to hold on to every last drop. Along New Mexico's drought-plagued Rio Grande, for example, farmers threatened with federally enforced irrigation cuts to help save an endangered minnow have refused a government offer to pay them not to plant this season. "We don't want their money; we just want them to leave us alone and let us farm," says Corky Herkenhoff, who owns a 600-acre alfalfa farm near San Acacia.

The drought, however, may have hurt the farmers' case. With low river flows killing thousands of minnows, "the drought has dramatically raised public awareness about the plight of the river," says John Horning, executive director of the Forest Guardians, a Santa Fe-based nonprofit that has waged a legal campaign to help save the rare minnow. Horning points to a recent University of New Mexico study showing that 80 percent of state residents support measures to ensure the river's flow. "In the past, people didn't have to choose between an alfalfa field and a healthy river," says Horning, but now that they're forced to, "they're increasingly choosing the river."

With another meager mountain runoff this spring, Ken Maxey, a federal Bureau of Reclamation manager in Albuquerque, says he had little choice but to warn Rio Grande-area farmers that if they don't stop diverting river water he might have to force them to do so. "That's when the war is going to start around here," warns Herkenhoff. "We may not sit on the head gates with a shotgun, but we'll get out and raise some hell."

In fact, it may be all over but the shouting. Although the Old West holds prior claims to the region's water, the New West increasingly has the political and financial clout to determine how and where the water gets used. And as the continuing drought raises the stakes for everyone, more fields are likely to go fallow so that the Rio Grande's minnows can survive and people like Ed Wirth can keep their backyards green.