Memorial Day Weekend 1983: Streets to Rivers

LeRoy W. Hooton, Jr.

May 28, 1999

As the snowpack melts this spring of 1999, we are reminded of the spring of 1983, when Salt Lake City's streets were made into rivers. This paper reminisces about that spring 16 years ago when flooding occurred in Salt Lake City, and in the aftermath, extensive flood control improvements were made, including the construction of Little Dell Dam and Lake Project in Parleys Canyon.

The Wet Season

The 1981- 82 Salt Lake area water year ended with a bang during the fall of 1982. A record-breaking 3.72 inches of precipitation hit the Salt Lake valley from Saturday September 25 to Tuesday September 28, 1982 causing widespread flooding. This was called a once in every 100 years storm. Described in the Deseret News, “the deluge Sunday, (was) termed the worst in Salt Lake County history, flooding more than 1,000 homes and forced the evacuation of 200 to 400 people. It sent down mud and rock slides, closing Big and Little Cottonwood canyons.” The City’s Big Cottonwood Water Treatment Plant was shut down by a landslide inundating parts of the plant with 4-feet of mud, but causing no structural damage. It was the third time during the year that heavy rains had forced the closure of this treatment facility. Likewise the City’s Wastewater Treatment Plant received flows far in excess of its capacity, and a plea was sent out to city residents not to use their toilets or indoor plumbing until the surge resided. It was estimated that over 100 million gallons per day was being processed in the 56 million-gallon capacity plant. September 1982 was the wettest ever on record, and the water year ended with a record 24.40 inches of precipitation, more than 9 inches above the average.

Above Normal Winter Snowpack

The wet September was the harbinger of more wet weather to come. The winter months produced copious amounts of precipitation and snowpack. The wet cycle began to affect the water elevation in the Great Salt Lake. As early as December 1982, there were predictions that the lake could rise from 4,202 to an elevation of 4,210 during the decade. Early on there were discussions about a lake pumping plan.

According to the USGS California, Nevada and Utah experienced one of the most severe winters since the agency began collecting climatic data in the 1880s. Above normal snowpack and cool temperatures delayed the snowmelt until late May, when temperatures rose to the 80s.

In western Nevada saturated soils caused slope failure in the Sierra Nevada area. On Memorial Day, a massive landslide on the flank of Slide Mountain displaced two small lakes and sent a peak 30,000 cubic feet per second mud and debris flow roaring down Ophir Creek into Washoe Valley between Carson City and Reno. The Truckee River flow reached 2,000 cubic feet per second, nearly three times its normal flow.

|

The 1983 Spring Run-off

In mid April a giant wall of muddy earth from the Thistle slide in Spanish Fork Canyon blocked the Spanish Fork River, creating a natural reservoir, which inundated 22 homes in the town of Thistle.

In the Salt Lake area, the first sign of a problem occurred in late April when Emigration Canyon Road near the mouth of the canyon became a gapping 40–foot hole. According to Neil Stack, Salt Lake County Flood Control, “the massive crater was created when water from the surrounding hillsides seeped deep into the ground until it stopped behind a natural sandstone table and an impenetrable layer of soil under the road.” There were also slides on East Capitol Boulevard near the mouth of City Creek canyon.

During early May rain showers and low elevation snowmelt caused minor flooding along 1300 South, beneath which runs the drainage of Red Butte, Emigration and Parleys Creeks through a storm drain conduit. Rains also caused flooding on Red Butte at Princeton Avenue and McClelland Street. The full 13th South conduit impeded the releases of water from Mt. Dell Reservoir in Parleys Canyon. On April 29, 1983 a meeting was held in the office of Salt Lake City Mayor Ted Wilson to discuss the potential of flooding and the difficulty of releasing water from Mt. Dell Reservoir. Terry Holzworth, director of County Water Quality and Flood Control talked about intentionally flooding areas along 13th South west of State Street. LeRoy W. Hooton, Jr., director of Salt Lake City’s Public Utilities, noted that the reservoir was already half full, and it should be empty to be able to store the expected run-off. He said, “We have only been able to take about 100 second-feet out of the reservoir. Normally we would be taking 150 to 200 second-feet out.” It was agreed in order to reduce major flooding later, to force as much water as possible down the 1300 South Conduit. Salt Lake County Flood Control dredged the Jordan River in anticipation of high spring run-off.

Making Streets into Rivers

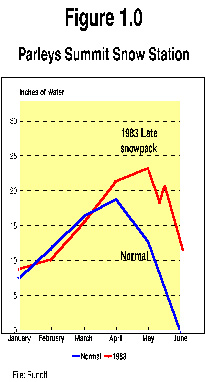

The conditions leading up to the Memorial Day weekend of 1983 can be described by viewing the Parleys Summit Snow Survey data (See Figure 1). While the May showers complicated the releases of water from Mt. Dell Reservoir and caused some local flooding, the growing snowpack in the Wasatch Mountains and cooler temperatures were building for a rapid run-off during late May and early June. As Figure 1 demonstrates, the water content in the snowpack continued to increase (above normal) until early May and began to diminish until mid-May when the anomaly occurred. The water content began to rise to over 20 inches instead of being reduced to nearly zero by June 1. This delayed melt, plus the high water content, led to making Salt Lake City’s streets into rivers.

On May 26, 1983 at a hastily called meeting Salt Lake City declared an emergency and decided to dike 1300 South in order to convey flood waters from Red Butte, Emigration and Parleys Canyons to the Jordan River. The morning paper, (Salt Lake Tribune) read, “Mayor Calls Emergency, As Waters Flood Street.” The story read, “The mayor after considering options and the impact of allowing Mountain Dell Reservoir in Parleys Canyon to overflow, made the proclamation of emergency in order to begin immediate sandbagging for berms and to start the work

|

On May 28, 1983, the dike was completed and 300 cubic feet per second of water was released from Mt. Dell to gain control over the level of water in the reservoir storage area. “Before the release three times the amount of water was coming into the reservoir than going out,” said Al Haines, Salt Lake City chief administrative officer.

Statewide flooding occurred. In Juab County water was covering I-15. In Provo Canyon SR 92 was closed due to flooding. Floodwaters were flowing in the Weber and Ogden Rivers. Mudslides were common throughout the state from saturated soils. Diking was necessary to keep Utah Lake from inundating I-15 south of Provo. Some flooding occurred in every county.

No sooner had the run-off from Red Butte, Emigration and Parleys Canyons been contained in the man-made 1300 South river, than City Creek became a problem. On Sunday May 29, 1983 City Creek jumped out of its banks in Memory Grove and started to flood the downtown business district of Salt Lake City. The City Creek storm drain conduit had plugged from sand, gravel and debris, forcing the water onto the street. A call went out for volunteers to sand bag about 1-1/2 miles of State Street to 4th South where the floodwater could be conveyed to the Jordan River. It was estimated that about 6,000 volunteers responded. Later this volunteer response was described by Mayor Wilson, as “the biggest street festival ever.” Later it would be necessary to extend the sandbags to 9th South. The City Creek Water Treatment Plant was taken out of service as the intake and coagulation basins filled with grit. City Creek Canyon was heavily damaged from the floodwaters.

Trained City employees worked long and hard to control the floods. An example of an individual effort was an instance that occurred on Creek Road. As the City Creek flood waters spilled onto Creek Road below Memory Grove it carried with it high concentrations of grit and silt debris (the same material that had plugged the storm drain conduit). Canyon Road eroded, washing a gapping hole in the road, exposing a sanitary sewerline and breaking it. The heavy concentration of grit and silt was entering the sewerline and had the potential of plugging the entire sewer system within the main business district. If this had occurred it could have closed the area for business until the sewer system was cleaned and usable. Marvin Johnson, a Public Utilities sewer worker braved the fast moving water on Creek Road and climbed down a manhole and placed a sand bag into the sewer pipe and scurried out before the manhole filled with water. Although many citizens lined the street, including councilperson Sydney Fonnesbeck, most did not realize what the consequences would have been if the action had not been taken.

|

During the flood period, volunteers played a key role in managing the situation. An estimated 50,000 person days of effort in Salt Lake City and about twice that amount in the remainder of the county were utilized in flood control efforts. This was estimated to be valued at $18 million. In the county 1.6 million sandbags were filled and placed, and another million in Salt Lake City.

Record Flows and Damage

Salt Lake City is located on the edge of the Great Basin Desert. It’s not accustomed to high flood waters. The volumes of water that flooded Salt Lake City during the Memorial Day weekend of 1983 by most standards were not large. In other parts of the United States thousands of cubic feet of water flow is not uncommon. Flooding on the Missouri or Mississippi can inundate thousands of acres of land. Nevertheless, the spring floods of 1983 affected most of the western United States and within Salt Lake County caused millions of dollars in damage. Salt Lake County Flood Control identified 1,500 damaged sites at an estimated $34 million. Statewide the estimated damage costs reached $200 million. President Reagan granted Tooele, Garfield, Box Elder, Piute, Summit, Carbon, Emery, Utah, Davis, Millard, Weber and Salt Lake Counties disaster status.

Parleys Creek peaked on May 29, 1983 at 605 cubic feet per second 3.8 times its 160 cubic feet per second flood stage. This flow occurred when Mt. Dell was nearly full and unable to store the high peak flow. City Creek peaked on June 2, 1983 at 305 cubic feet per second, a flow 3.38 times its flood stage of 90 cubic feet per second and nearly double the record of 158 cubic feet per second that occurred in 1921.

The Aftermath

|

The flood gave the final impetus to construct the Little Dell Dam and Reservoir in Parleys Canyon – Dell Fork, up-stream of the inadequate Mt. Dell Dam and Reservoir. Completed in 1992, this flood control and water supply project will greatly minimize the need to ever make 1300 South a river again.

The 1983 flood was the beginning of a 4 year wet cycle that would cause the Great Salt Lake to rise to the 4211.6 elevation in the spring of 1986. The Great Salt Lake Pumping Plant was constructed by the state to control the level of the lake. This facility operated for some time, and it will be available in future years, if the lake rises again.

A Great Effort By All

Public employees responded to the emergency situation, providing the leadership to first manage the floods and then make the necessary repairs. Volunteers played a key role in responding to flood threat. National attention to the flooding highlighted the community’s volunteerism efforts in time of need.

Mayor Ted Wilson praised employees, volunteers, businesses, church and civic groups for their efforts. A resolution was passed by the City Council. Mayor Wilson said, “In recognition of (their efforts) a resolution was issued by the City Council and myself on June 7, 1983, to attempt to express our heartfelt appreciation for all who were involved in fighting the flood waters.”

Questions regarding this article can be directed to: leroy.hooton@ci.slc.ut.us

Selected References

United States Geological Survey Year Book, FY 1983, p.8

Ibid, p. 11

Salt Lake Tribune, April 25, 1983, “Crews Struggle With Emigration Canyon Repair” Doug Clark

Deseret News. April 30, 1983, “S.L. area may be flooded as preventative measure” Lee Davidson

Salt Lake Tribune, May 27, 1983, “Mayor Calls Emergency, As Waters Flood Street” Jon Ure

Salt Lake Tribune, May 28, 1983, “Spring Run-off Hits Us Hard”

Deseret News, June 26, 1983, “It took planning, but lots of help, it worked.

Effective Emergency Response, Retrospect Report No. 1, Public Works Historic Society, p.11

Ibid, p.12

Ibid, p.12

www.slcclassic.com/services/utilities/news030449html (for more information on the Great Salt Lake)

Official Rumor, July 1983, “Beating the Floods,” by Mayor Ted Wilson