The Great Salt Lake

The Remnants of Lake Bonneville

March 3, 1999

|

|

Early Explorations

Jim Bridger once believed that the lake was an arm of the Pacific Ocean; however this was disproved in 1825 at a trapper rendezvous held at the mouth of the Weber River. Trapper John Ashley’s men were curious about the lake, so four of them took 24 days to boat around the body of water. They learned that it was indeed a lake, estimated to be 100 miles long and between 60 and 80 miles wide. Without instruments, their estimated size of the lake was surprisingly accurate.

The mountain men and trappers of this era were not educated and their knowledge of the area was not chronicled. This was left up to the U.S. government. Captain B.L.E. Bonneville was the first government representative to explore the region between 1832 and 1836. He made one of the early maps of the whole basin. In 1837, Washington Irving published a book, using in part Bonneville's journal and map. This made Bonneville famous, resulting in the pre-historic lake being named after him.

Captain John C. Fremont made his first exploration in 1843, followed by two others; one in 1845 and another in 1853. Fremont was credited as the first to publish his scientific observations of the lake. For example, after 5 days of exploring the lake, he wrote, "Immediately at our feet (we) beheld the object of our anxious search--the waters of the Inland Sea, stretching in still and solitary grandeur far beyond the limits of our vision." He continued likening the experience to that of Balboa (A Spanish explorer who in 1513 claimed the Pacific Ocean in the name of Spain), "It was one of the greatest points of the exploration; and as we look eagerly over the lake in the first emotions of excited pleasure, I'm doubtful if the followers of Balboa felt more enthusiasm when, from the heights of the Andes, they saw the first time a great Western ocean. It was certainly a magnificent object, and a noble terminus to this part of the expedition."

In April 1849, Captain Howard Stansbury, topographical engineer, was ordered from Fort Leavenworth to make a survey of the Great Salt Lake, an exploration of its valley and to find the route for a transcontinental railroad. Begun one year later, Stansbury and a cadre of local laborers, along with three other diarists; Lieutenant John William Gunnison, surveyor and second in command; John Hudson, draftsman and Albert Carrington, Brigham Young's private secretary, completed the work of surveying the lake in 3 months. Twenty-four triangulation stations were erected to survey the lake, the shoreline and the islands. Stansbury is credited with the scientific measurement of the lake and its natural wonders.

Fluctuations in Lake Level

On average 2,000,000 acre-feet of water flows into the lake from 3 main tributaries, the Jordan River (20%), Weber River (22%), Bear River (56%) and other sources (2%).

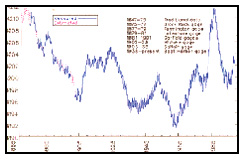

The lake level is regulated by the amount of flow and the evaporation rate. Therefore, the lake elevation varies, depending on the precipitation, climate and temperature. Elevation records date back to 1850, shortly after the Mormon pioneers settled the area. The elevation at that time was 4210. It began to rise from that date, peaking at about 4212 in 1872. The elevation decreased until the early 1900s, when it again increased between 1910 and 1925. By the mid 1930s it dipped to approximately 4185, as a result of the severe drought of that period. In 1963 the lake was measured at its lowest point at 4191.6. As a result of the wet cycle of the 1980s, the lake rose to record heights in 1985-86. (See Chart)

|

Salty Water

Because the lake has no outlet, evaporation causes the water to have a salinity of over 20 percent, making it impossible to use for municipal water supply. The river tributaries carry large quantities of dissolved salts into the lake, and when the water evaporates, the salts are left behind. The salt concentrations (brine) vary with the amount of water flowing into the lake. During wet cycles the lake volume increases and the salt concentration is reduced. Conversely, during drought periods, the level recedes and the concentrations increase. The percentage of salt by weight was at its lowest concentration in 1873. The salinity was 10 percent with the lake elevation at 4211.7 feet and a total volume of 29.5 million-acre feet; it reached a high in 1963 of 27.5 percent salt by weight when the lake elevation was at 4191.6 feet and a total volume of 8.7 million-acre feet. The lake is famous for the fact that because of the salt content, swimmers can’t sink. In years past, most Utahns and visitors alike tested this and found themselves covered with white crusted salt upon drying out on the beach. The shoreline was a popular recreation area during the first half of this century, but in recent years it has lost its popularity.

The Recent Flood Years

In the 1980s there was great concern over the level of the lake and its impact on the airport, wastewater treatment plant, I–80, rail lines along the shoreline and the western part of Salt Lake City. The lake reached its record elevation during 1986-87, and there was concern if the wet cycle continued that many of these critical areas would be inundated with water from the lake. The 1982-83 snowpack run-off, measuring 265 percent of normal, produced widespread flooding throughout the State of Utah. This exacerbated the already in progress wet cycle that increased the lake level 12.2 feet between 1982 and 1986. Precipitation for the 7 years between 1979-1980 and 1985-1986 was 152 percent of normal.

With some predicting that the lake had a 90 percent probability of reaching 4215 feet, the state legislature approved the “West Desert Pumping Project” to control flooding around the lake, by constructing the Pump Station and dikes. Water was pumped from the Great Salt Lake to the west desert, where the pumped water was evaporated over a large west pond area. The Pump Station was built at a cost of $58 million and the first pump turned on during April, the second pump in May and the third during June 1987. After more than 2 years of operation, the plant was shut down on June 30, 1989. Over 2.2 million acre-feet of water was pumped during this period, or about 26 inches of water. The decision by the state to construct the pumping project provided a sigh of relief to those affected by the raising waters. Salt Lake City was considering a $10 million

|

The lake peaked at an elevation of 4211.85 during the spring of 1986, the highest level ever measured since the pioneers arrived in 1847. According to the State Department of Natural Resources June 26, 1989 news release, “Economic losses to state, federal, and private interests between 1983 and 1986 was an estimated $240 million.” For example, it was reported that the Union Pacific had spent $87 million raising the tracks along the south shoreline, and the U.S. Department of Transportation $300,000 in raising the I-80 roadbed.

Of major concern to Salt Lake City was its wastewater treatment plant located at 2300 North. The plant operating effluent high water elevation is 4215.02. At the 1986 lake level, windstorms from the north would force a 2 to 3 foot wave of water up the outfall canal (Oil Drain - Salt Lake City Sewage Canal), affecting the free flow of water from the plant. As part of the lake control projects, a dam was built across the outfall canal and a pump plant built to lift the water to the downstream side of the dam. This allowed the wastewater treatment plant to operate and meet its NPDES permit limitations.

The Great Salt Lake followed its historic pattern of varying elevations and began receding during the late 1980s and 1990s. A drought cycle began in 1988 and continued through the early 1990s. The lake level is currently at about 4203 elevation and not causing any problems.

Primary Uses of Lake

The lake and surrounding shore area supports many types of wildlife, recreation and mineral production. It is estimated that three million game birds migrate through the area to the south. Mineral extraction from the lake includes common salt, salt cakes, sulfate of potash (fertilizer), and magnesium chloride. Sail boating is a popular recreational use of the lake. In recent years, harvesting brine flies for fertilizer has grown as a commercial endeavor.

1998 Great Salt Lake Comprehensive Management Plan

|

In recent times there has been growing concern over the salt concentration between the southern part of the lake and the divided northern part of the lake. The Southern Pacific Railroad causeway has created two different lakes. The north side is more saline, while the south is less saline. During 1998 the Utah Department of Natural Resources prepared the Great Salt Lake Comprehensive Management Plan to address the water quality and environmental issues associated with the lake. Particularly the difference in salinity in the south part of the lake which about 9 percent versus the north that is 28 percent. The lower salinity in the south is affecting the brine-shrimp product in this portion of the lake.

Conclusion

The prominence of the Great Salt Lake will continue into the future, both in terms of its physical presence and in its recreational, commercial and environmental benefits. If history is a guide to the future, the lake will continue to vary in elevation and size with the changing weather patterns. Some day in the future, the Great Salt Lake pumps will again be started to control the lake elevation and potential flooding.

Additional Information can be requested by e-mailed to: leroy.hooton@ci.slc.ut.us

Selected Bibliography

Aquarius, The Great Salt Lake, May 1977 Utah State University, Logan, Utah

Exploring the Great Salt Lake, The Stansbury Expedition of 1849-50, Edited by Brigham D. Madsen

History of Utah, Bancroft

Salt Lake County Area-Wide Water Study, April 1982

Utah and Her Western Setting, by Hunter

Utah Division of Water Resources, news released dated June 26, 1989